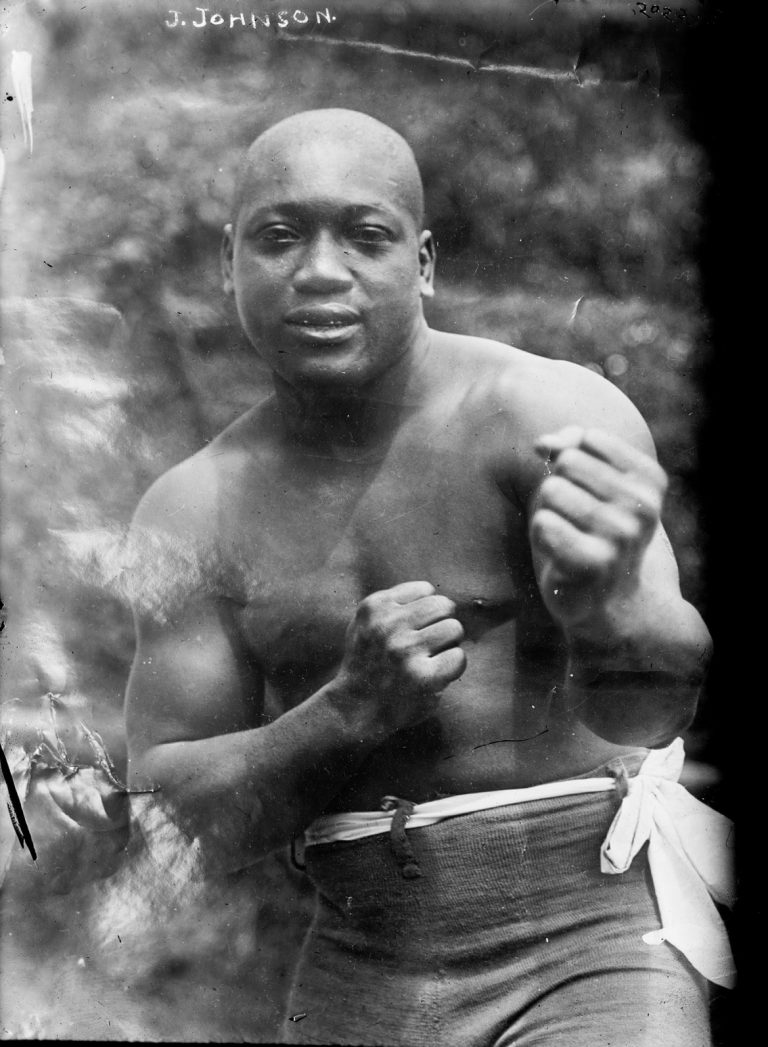

“I’m Jack Johnson, heavyweight champion of the world! I’m black! They never let me forget it. I’m black all right. I’ll never let them forget it.” Jack Johnson

“Johnson was a black man who lived by his own rules, who conquered the white man on his own terms, and never let anyone tell him what to do. That’s the way I want to play my music—strong, fast, and without apology.” Miles Davis

Jazz, often hailed as America’s most significant cultural contribution, emerged from the deep well of African American experience. It is a music that speaks to the soul, a spontaneous yet structured form of expression that mirrors the complexity of life itself. For the Black community, jazz was not just music—it was a voice in a society that tried to silence them – the Jim Crow era where white supremacy ruled and was often lethal.

Musicians like Davis, whose innovations in jazz pushed the boundaries of the genre, used their craft to articulate the struggles and aspirations of Black Americans against this opposing force, nowhere more vividly expressed than when Miles was attacked, beaten and arrested by two white cops outside the famous jazz club, Birdland, in NYC in 1959. This had happened after Miles had walked a white lady to a cab and was taking a cigarette break between live sets – his name plastered in lights above the club door; the assault occurred just eight days after the release of his seminal album: ‘Kind of Blue’ – ranked as the greatest jazz album of all time.

Jack Johnson, son of a slave, and Miles Davis, son of a middle-class dentist who paid for him to attend the prestigious Julliard college of Music in NYC, both had a visceral understanding of the racial (anti-Black) politics of their times and it was a large part of what drove them to succeed. Both were alpha males who loved women – white, black or brown – and who had an acute appreciation of style – fast cars, fine clothes, and fine liquor. Miles had once said that “Johnson portrayed Freedom — the more they hated him, the more money he made, the more women he got and the more wine he drank.” Let’s not forget, Jack Johnson was born in Texas in 1878 and died in 1946 but that he reigned as Heavyweight champion of the world at the very height of the Jim Crow era from 1908 to 1915. The ‘Galveston Giant’s’ achievements inside the ring and his lifestyle outside it were considered an outrage to the vast majority of white folks at the time, something Miles Davis would also represent during the 50s and 60s in America.

Davis’s love for boxing, particularly his admiration for Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight champion, is a testament to the deep connection between these two worlds. Johnson, much like Davis, was a pioneer who broke through racial barriers, challenging the status quo. Davis, a boxer himself, found in boxing a rhythm and a discipline that paralleled his musical genius. The timing, the precision, the ability to anticipate and react—these were qualities Davis admired in Johnson and emulated in both the ring and on stage. Boxing, like jazz, required improvisation, an ability to adapt and respond in the moment—qualities that both Davis and Johnson mastered. Davis said, “Both boxing and jazz demand the same kind of timing and reflexes. You can’t just go in there swinging or blowing. You gotta be sharp, alert, and in control.”

Fun fact: Miles Davis used to train at Gleason’s Gym in New York City back in 1970. “Before performances, Miles stayed away from others and often drove away anyone who might approach him. Like a boxer, preparing for a fight, he denied himself food and sex before playing, believing that a musician should perform hungry and unsatisfied.” (excerpt from “So What: The Life of Miles Davis”: John Szwed (2002).

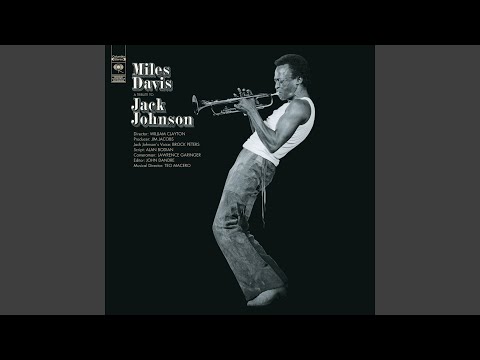

In 1970, Davis was asked by boxing promoter Bill Cayton to record music for a documentary he was making, on the life of boxer Jack Johnson, to which Miles duly obliged: ‘A Tribute to Jack Johnson”- released, 1971 – became a jazz fusion classic. The link below is the first track of the album called ‘Right Off’ which sees some incredible interplay between the guitar (John McLaughlin) and the trumpet (Miles) which Davis likened to two boxers going at it.

Jazz improvisation is the delicate dance between art and science, a fusion of disciplined technique and creativity. At its core, jazz is a conversation—a spontaneous exchange of ideas between musicians, where each note is both a response to the last and an invitation to the next. It’s a language of intuition, where the rules are known but often bent, and where the beauty lies not just in the notes played, but in the spaces left between them. Miles had famously said, “It’s not the notes you play; it’s the notes you don’t play.”

In many ways, boxing is a similar blend of art and science. A boxer, like a jazz musician, must master the fundamentals—the jab, the hook, the footwork, the feints. But in the ring, just as in a jazz club, these fundamentals are only the beginning. The true artistry of boxing lies in the fighter’s ability to improvise, to read an opponent’s intentions in a split second, and to respond with a combination of skill and creativity. It’s a fluid, dynamic dance where rhythm is everything, and timing can be the difference between success and failure. Recall, if you will, the extraordinary uppercut Bud Crawford landed on Spences’ jaw, a nanosecond before Errol’s massive overhand left landed on the side of Bud’s head. Down went Spence, just like that. It was beautiful to watch – especially in slow motion. Timing in both jazz and boxing is everything.

A boxer, much like a jazz musician, also relies on intuition—the ability to sense the unseen, to anticipate the next move, and to react in the blink of an eye. In the ring, every punch thrown is both a calculated decision and a leap of faith, much like a note played in a jazz solo. The boxer reads the opponent’s body language, picks up on the smallest of cues, and adjusts strategy on the fly. This is the science of boxing—studying the opponent, understanding angles, and knowing when to strike. But it’s also an art, where instinct and experience blend to create something unpredictable and beautiful.

Both jazz and boxing celebrate the moment—the instant where preparation meets opportunity, where a lifetime of practice comes down to a single, defining action. In jazz, it’s the note that hits just right, the phrase that brings the house down. In boxing, it’s the perfectly timed punch, the movement that leaves the opponent open and vulnerable. Both forms of expression demand not just physical prowess but emotional and intellectual engagement, where the practitioner must be fully present, ready to adapt, and willing to take risks.

Miles Davis had a deep appreciation for boxing, seeing it as not only a physical activity but also as an art form that paralleled his approach to music, particularly jazz. Ultimately, both jazz and boxing are expressions of the human spirit—testaments to our capacity for creativity, resilience, and calm under pressure. They are reminders that, whether in music or in the ring, it’s not just about following the script; it’s about writing your own, one note or one punch at a time.